I was studying reinforcement learning a while ago, attempting to educate myself about deep Q learning. As part of that effort, I read through the first few chapters of Reinforcement Learning: An A Introduction by Sutton and Barto. Here are my notes on Chapter 1. Like all of my other notes, these were never intended to be shared, so apologies in advance if they make no sense to anyone.

Chapter 1

This chapter is mostly nontechnical intro material. There are a few key definitions however.

What is RL

In a single sentence, it is goal-directed learning through trial and error.

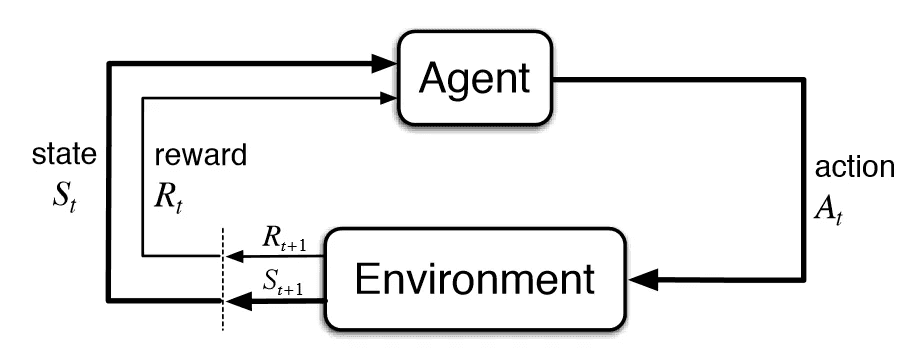

How does it differ from supervised learning? Rather than a machine being shown what to do, the machine is given a feedback signal in the form of a reward. Thus an agent learns by exploring actions and their associated rewards, and by modeling the expected long term reward for actions given states. The notions of trial end error search and delayed reward are the important features that distinguish RL from traditional machine learning.

Key Notions for RL

- State - A representation of the task at a given time. For example, if the task is a game, then the state might be a screenshot of the game.

- Action - an action that the agent may take. Policy - a mapping from the state space to the space of probability distributions on the action space. This could be a lookup table (methods with tabular policies are called tabular methods), or it could be a complex, even stochastic, search algorithm. * Agent - A process for sampling from the set of actions according to a distribution, which is afforded by the policy.

- Reward - Defines the goal of the algorithm. Each time step, the environment sends the agent a single reward value. The agent's objective is to maximize the total sum of reward over time.

- Value - A function from the state space to the expected total sum of reward starting from that state, given a policy.

A note on genetic algorithms

Directly from the book:

Most of the reinforcement learning methods we consider in this book are structured around estimating value functions, but it is not strictly necessary to do this to solve reinforcement learning problems. For example, solution methods such as genetic algorithms, genetic programming, simulated annealing, and other optimization methods never estimate value functions. These methods apply multiple static policies each interacting over an extended period of time with a separate instance of the environment. The policies that obtain the most reward, and random variations of them, are carried over to the next generation of policies, and the process repeats.

Tic Tac Toe Example

This section outlines an example of an RL algorithm on Tic Tac Toe. In this example, it is important to note that the policy evolves while the game is played, a key contrast to the genetic algorithms above (in which static policies are scored and then the best are selected to inform subsequent generations).

In this example, states are snapshots of the game at the time of the agent's move. We will learn a value function which represents the probability of winning the game (the policy depends on the value function). Since the state space is small, we initialize a table of numbers, one for each state. In it, the winning states have value equal to 1, and the loss and draw states have value 0. All other states are initialized at 0.5. We then play many games against an opponent (another agent or human player). The policy is set by considering the possible moves at time and selecting the most valuable move with probability , with the other moves selected uniformly at random with total probability . Whenever a greedy move is made, we update the value at time by adding a small fraction of the difference between the values at times and :

This process is called backing up the state after the move in the book. Something I find confusing is figure 1.1 on page 10. The arrows seem to indicate that we are backing up to two states back, which would seem to contradict the formula. However, I believe the figure is incorrect, based on a python implementation I found.

This algorithm is an example of temporal difference learning, which will be covered in later chapters.

Study Questions

Exercise 1.1: Self-Play

Suppose, instead of playing against a random opponent, the reinforcement learning algorithm described above played against itself, with both sides learning. What do you think would happen in this case? Would it learn a different policy for selecting moves?

Solution: There are two forces balancing each other out here. The skill of the agent being trained, and the skill of its opponent. Initially it should learn as before, since the opponent is imperfect. As the agent improves, so does its opponent (they are always the same). So if at some point, the model learns well enough to to never lose, then so will its opponent. In this case, every game will end in a draw (both players learn perfect strategies). At this point, the move sequences that lead to victory for the agent are no longer explored, so this behavior is not learned. Thus, it seems like the model should prevent itself from learning a perfect strategy.

Exercise 1.2: Symmetries

Many tic-tac-toe positions appear different but are really the same because of symmetries. How might we amend the learning process described above to take advantage of this? In what ways would this change improve the learning process? Now think again. Suppose the opponent did not take advantage of symmetries. In that case, should we? Is it true, then, that symmetrically equivalent positions should necessarily have the same value?

Solution: We can define the value function to respect the symmetries and this will reduce the number of parameters that need to be learned. This will allow for faster convergence to the optimal solution.

Exercise 1.3: Greedy Play

Suppose the reinforcement learning player was greedy, that is, it always played the move that brought it to the position that it rated the best. Might it learn to play better, or worse, than a nongreedy player? What problems might occur?

Solution: It should learn worse behavior. It could find suboptimal solutions without ever exploring enough of the action-state space to find optimal solutions. This is analogous to getting stuck in local optima in supervised learning.

Exercise 1.4: Learning from Exploration

Suppose learning updates occurred after all moves, including exploratory moves. If the step-size parameter is appropriately reduced over time (but not the tendency to explore), then the state values would converge to a different set of probabilities. What (conceptually) are the two sets of probabilities computed when we do, and when we do not, learn from exploratory moves? Assuming that we do continue to make exploratory moves, which set of probabilities might be better to learn? Which would result in more wins?

Solution:

Exercise 1.5: Other Improvements

Can you think of other ways to improve the reinforcement learning player? Can you think of any better way to solve the tic-tac-toe problem as posed?

Solution: